Since he was young, Paul Asao has always loved beautiful things.

He credits this to the creatives in his life who showed him how to express a passion for arts, including his mother, Rose. She was a talented artist who used art, including sumi-e paintings (Japanese ink painting) and calligraphy, to honor her Japanese American heritage.

Now as a creative director for Best Buy Creative Services, Paul is constantly creating and using art to tell the Best Buy story.

“A close friend of mine in the advertising industry once told me, ‘Never stop doing what you like or want to do,’” Paul said. “That really stuck with me.”

For most of his childhood, Paul never thought too much about his Japanese American heritage, even as he and his family were one of only two families of color in his childhood school district. But Paul says he never felt any obvious discrimination. He felt like a normal kid.

It wasn’t until he became a teenager that Paul noticed his father, Theodore, would ask every Japanese American around his father’s age which camp they were from. He was referring to the internment camps where almost 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — most of whom were American citizens — were forced to relocate during World War II.

“At first, I thought he meant a summer camp,” he said. “It wasn’t until I was in high school that my father told us what it meant.”

That opened the conversation among Paul, his siblings and his parents into their heritage and what it has meant for both of his parents living in the United States.

Paul’s family history

Theodore grew up in Los Angeles, and when WWII began, he was sent to an internment camp in Poston, Arizona, with his parents and younger brother. They were given 24 hours to sell or entrust their business and home to someone else and packed what they could take on a train.

“I think many other Japanese American families had a similar experience,” Paul said. “My father’s family was only able to take two suitcases on the train when they left.”

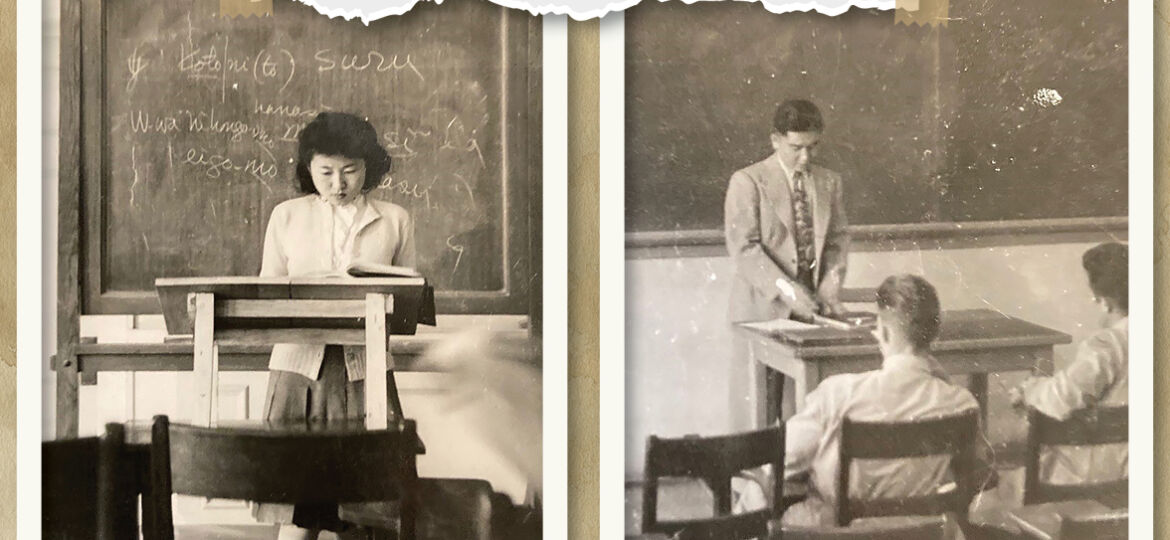

After two years in the camp, Theodore was recruited by the U.S. military and deployed to Minnesota, to serve at a Military Service Intelligence School. He taught Japanese to U.S. officers and assisted with decoding and translations.

Theodore’s situation isn’t unique. Many Japanese Americans were transferred from internment camps, leaving their families behind, to assist the U.S. in the war. However, the schools were considered classified, and it wasn’t until years after the war that people learned what Japanese Americans had done for the U.S. military.

After the war, Theodore stayed in Minnesota and decided to go to pharmacy school, where he met his wife, Rose, who also is a second-generation Japanese American.

Despite a difficult time in Japanese American history, Paul says his father, who has now passed away, didn’t recall his experience during his internment with anger or sadness.

“He was a glass-half-full type of person,” Paul said. “He always said the silver lining after the war was he was able to meet my mother since he was in Minnesota. He considered it a positive thing.”

Exploring the meaning of his heritage

After Paul graduated from college, he became more interested in discovering more about his Japanese heritage. That led him to The Nikkei Project, which helps younger Japanese Americans connect with their elders.

“Connecting with the older generations has made me proud of my heritage,” Paul said. “I’ve met a lot of examples of people who’ve faced adversity in their life. They’re such a joyful group of people that have contributed a lot to society and their communities.”

A large portion of the Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) were interned like Paul’s father and experienced increased discrimination during and following WWII. Paul has met Japanese Americans who served in U.S. army in Germany during the war and others who were in Japan at the time.

As a Sansei (third-generation Japanese American), Paul says he enjoys hearing the stories from his elders and is continuously inspired by the generation’s outlook on the war.

“Life is too short to hold a grudge and hang onto things you cannot change,” Paul said. “This is a philosophy I’ve learned from my heritage — from my parents and all of the people I’m fortunate to meet through The Nikkei Project.”

Inspired to give back

Paul remembers his parents always volunteering and helping around the community. His father was a Boy Scouts troop leader and involved with his church, and his mother was a schoolteacher for years. This strong commitment to serve others is another lesson Paul has taken with him into his adult life.

In addition to his work with The Nikkei Project, Paul has used his creative and branding expertise to support Seattle’s Union Gospel Mission. The organization provides food, shelter and services to the homeless population in Seattle.

For more than six years, Paul has spent his spare time and paid time off visiting Seattle and creating branding for the organization. He’s even gained national attention for the cause through some high-profile creative partnerships.

At this point in Paul’s life, he’s focused on what he can do to make his community better, rather than seeking the next ambitious project. At Best Buy, he’s inspired by his team and the creative solutions they’ve produced, especially by the recent holiday campaign created in the wake of the pandemic.

“I’d like to use my talents if there’s an opportunity to help,” he said. “I’d encourage others to see what they can do to make our community less divisive.”

Click here to visit our Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month landing page on BestBuy.com.